Warning: This notebook needs a running kernel to be fully interactive, please run it locally or on mybinder.

Jupyter integration: interactivity¶

Vaex can process about 1 billion rows per second, and in combination with the Jupyter notebook, this allows for interactive exporation of large datasets.

Introduction¶

The vaex-jupyter package contains the building blocks to interactively define an N-dimensional grid, which is then used for visualizations.

We start by defining the building blocks (vaex.jupyter.model.Axis, vaex.jupyter.model.DataArray and vaex.jupyter.view.DataArray) used to define and visualize our N-dimensional grid.

Let us first import the relevant packages, and open the example DataFrame:

[1]:

import vaex

import vaex.jupyter.model as vjm

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

df = vaex.example()

df

[1]:

| # | id | x | y | z | vx | vy | vz | E | L | Lz | FeH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1.2318683862686157 | -0.39692866802215576 | -0.598057746887207 | 301.1552734375 | 174.05947875976562 | 27.42754554748535 | -149431.40625 | 407.38897705078125 | 333.9555358886719 | -1.0053852796554565 |

| 1 | 23 | -0.16370061039924622 | 3.654221296310425 | -0.25490644574165344 | -195.00022888183594 | 170.47216796875 | 142.5302276611328 | -124247.953125 | 890.2411499023438 | 684.6676025390625 | -1.7086670398712158 |

| 2 | 32 | -2.120255947113037 | 3.326052665710449 | 1.7078403234481812 | -48.63423156738281 | 171.6472930908203 | -2.079437255859375 | -138500.546875 | 372.2410888671875 | -202.17617797851562 | -1.8336141109466553 |

| 3 | 8 | 4.7155890464782715 | 4.5852508544921875 | 2.2515437602996826 | -232.42083740234375 | -294.850830078125 | 62.85865020751953 | -60037.0390625 | 1297.63037109375 | -324.6875 | -1.4786882400512695 |

| 4 | 16 | 7.21718692779541 | 11.99471664428711 | -1.064562201499939 | -1.6891745328903198 | 181.329345703125 | -11.333610534667969 | -83206.84375 | 1332.7989501953125 | 1328.948974609375 | -1.8570483922958374 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 329,995 | 21 | 1.9938701391220093 | 0.789276123046875 | 0.22205990552902222 | -216.92990112304688 | 16.124420166015625 | -211.244384765625 | -146457.4375 | 457.72247314453125 | 203.36758422851562 | -1.7451677322387695 |

| 329,996 | 25 | 3.7180912494659424 | 0.721337616443634 | 1.6415337324142456 | -185.92160034179688 | -117.25082397460938 | -105.4986572265625 | -126627.109375 | 335.0025634765625 | -301.8370056152344 | -0.9822322130203247 |

| 329,997 | 14 | 0.3688507676124573 | 13.029608726501465 | -3.633934736251831 | -53.677146911621094 | -145.15771484375 | 76.70909881591797 | -84912.2578125 | 817.1375732421875 | 645.8507080078125 | -1.7645612955093384 |

| 329,998 | 18 | -0.11259264498949051 | 1.4529125690460205 | 2.168952703475952 | 179.30865478515625 | 205.79710388183594 | -68.75872802734375 | -133498.46875 | 724.000244140625 | -283.6910400390625 | -1.8808952569961548 |

| 329,999 | 4 | 20.796220779418945 | -3.331387758255005 | 12.18841552734375 | 42.69000244140625 | 69.20479583740234 | 29.54275131225586 | -65519.328125 | 1843.07470703125 | 1581.4151611328125 | -1.1231083869934082 |

We want to build a 2 dimensinoal grid with the number counts in each bin. To do this, we first define two axis objects:

[2]:

E_axis = vjm.Axis(df=df, expression=df.E, shape=140)

Lz_axis = vjm.Axis(df=df, expression=df.Lz, shape=100)

Lz_axis

[2]:

Axis(bin_centers=None, exception=None, expression=Lz, max=None, min=None, shape=100, shape_default=64, slice=None, status=Status.NO_LIMITS)

When we inspect the Lz_axis object we see that the min, max, and bin centers are all None. This is because Vaex calculates them in the background, so the kernel stays interactive, meaning you can continue working in the notebook. We can ask Vaex to wait until all background calculations are done. Note that for billions of rows, this can take over a second.

[3]:

await vaex.jupyter.gather() # wait until Vaex is done with all background computation

Lz_axis # now min and max are computed, and bin_centers is set

[3]:

Axis(bin_centers=[-2877.11808899 -2830.27174744 -2783.42540588 -2736.57906433

-2689.73272278 -2642.88638123 -2596.04003967 -2549.19369812

-2502.34735657 -2455.50101501 -2408.65467346 -2361.80833191

-2314.96199036 -2268.1156488 -2221.26930725 -2174.4229657

-2127.57662415 -2080.73028259 -2033.88394104 -1987.03759949

-1940.19125793 -1893.34491638 -1846.49857483 -1799.65223328

-1752.80589172 -1705.95955017 -1659.11320862 -1612.26686707

-1565.42052551 -1518.57418396 -1471.72784241 -1424.88150085

-1378.0351593 -1331.18881775 -1284.3424762 -1237.49613464

-1190.64979309 -1143.80345154 -1096.95710999 -1050.11076843

-1003.26442688 -956.41808533 -909.57174377 -862.72540222

-815.87906067 -769.03271912 -722.18637756 -675.34003601

-628.49369446 -581.64735291 -534.80101135 -487.9546698

-441.10832825 -394.26198669 -347.41564514 -300.56930359

-253.72296204 -206.87662048 -160.03027893 -113.18393738

-66.33759583 -19.49125427 27.35508728 74.20142883

121.04777039 167.89411194 214.74045349 261.58679504

308.4331366 355.27947815 402.1258197 448.97216125

495.81850281 542.66484436 589.51118591 636.35752747

683.20386902 730.05021057 776.89655212 823.74289368

870.58923523 917.43557678 964.28191833 1011.12825989

1057.97460144 1104.82094299 1151.66728455 1198.5136261

1245.35996765 1292.2063092 1339.05265076 1385.89899231

1432.74533386 1479.59167542 1526.43801697 1573.28435852

1620.13070007 1666.97704163 1713.82338318 1760.66972473], exception=None, expression=Lz, max=1784.0928955078125, min=-2900.541259765625, shape=100, shape_default=64, slice=None, status=Status.READY)

Note that the Axis is a traitlets HasTrait object, similar to all ipywidget objects. This means that we can link all of its properties to an ipywidget and thus creating interactivity. We can also use observe to listen to any changes to our model.

An interactive xarray DataArray display¶

Now that we have defined our two axes, we can create a vaex.jupyter.model.DataArray (model) together with a vaex.jupyter.view.DataArray (view).

A convenient way to do this, is to use the widget accessor data_array method, which creates both, links them together and will return a view for us.

The returned view is an ipywidget object, which becomes a visual element in the Jupyter notebook when displayed.

[4]:

data_array_widget = df.widget.data_array(axes=[Lz_axis, E_axis], selection=[None, 'default'])

data_array_widget # being the last expression in the cell, Jupyter will 'display' the widget

Note: If you see this notebook on readthedocs, you will see the selection coordinate already has ``[None, ‘default’]``, because cells below have already been executed and have updated this widget. If you run this notebook yourself (say on mybinder), you will see after executing the above cell, the selection will have ``[None]`` as its only value.

From the specification of the axes and the selections, Vaex computes a 3d histogram, the first dimension being the selections. Interally this is simply a numpy array, but we wrap it in an xarray DataArray object. An xarray DataArray object can be seen as a labeled Nd array, i.e. a numpy array with extra metadata to make it fully self-describing.

Notice that in the above code cell, we specified the selection argument with a list containing two elements in this case, None and 'default'. The None selection simply shows all the data, while the default refers to any selection made without explicitly naming it. Even though the later has not been defined at this point, we can still pre-emptively include it, in case we want to modify it later.

The most important properties of the data_array are printed out below:

[5]:

# NOTE: since the computations are done in the background, data_array_widget.model.grid is initially None.

# We can ask vaex-jupyter to wait till all executions are done using:

await vaex.jupyter.gather()

# get a reference to the xarray DataArray object

data_array = data_array_widget.model.grid

print(f"type:", type(data_array))

print("dims:", data_array.dims)

print("data:", data_array.data)

print("coords:", data_array.coords)

print("Lz's data:", data_array.coords['Lz'].data)

print("Lz's attrs:", data_array.coords['Lz'].attrs)

print("And displaying the xarray DataArray:")

display(data_array) # this is what the vaex.jupyter.view.DataArray uses

type: <class 'xarray.core.dataarray.DataArray'>

dims: ('selection', 'Lz', 'E')

data: [[[0 0 0 ... 0 0 0]

[0 0 0 ... 0 0 0]

[0 0 0 ... 0 0 0]

...

[0 0 0 ... 0 0 0]

[0 0 0 ... 0 0 0]

[0 0 0 ... 0 0 0]]]

coords: Coordinates:

* selection (selection) object None

* Lz (Lz) float64 -2.877e+03 -2.83e+03 ... 1.714e+03 1.761e+03

* E (E) float64 -2.414e+05 -2.394e+05 ... 3.296e+04 3.495e+04

Lz's data: [-2877.11808899 -2830.27174744 -2783.42540588 -2736.57906433

-2689.73272278 -2642.88638123 -2596.04003967 -2549.19369812

-2502.34735657 -2455.50101501 -2408.65467346 -2361.80833191

-2314.96199036 -2268.1156488 -2221.26930725 -2174.4229657

-2127.57662415 -2080.73028259 -2033.88394104 -1987.03759949

-1940.19125793 -1893.34491638 -1846.49857483 -1799.65223328

-1752.80589172 -1705.95955017 -1659.11320862 -1612.26686707

-1565.42052551 -1518.57418396 -1471.72784241 -1424.88150085

-1378.0351593 -1331.18881775 -1284.3424762 -1237.49613464

-1190.64979309 -1143.80345154 -1096.95710999 -1050.11076843

-1003.26442688 -956.41808533 -909.57174377 -862.72540222

-815.87906067 -769.03271912 -722.18637756 -675.34003601

-628.49369446 -581.64735291 -534.80101135 -487.9546698

-441.10832825 -394.26198669 -347.41564514 -300.56930359

-253.72296204 -206.87662048 -160.03027893 -113.18393738

-66.33759583 -19.49125427 27.35508728 74.20142883

121.04777039 167.89411194 214.74045349 261.58679504

308.4331366 355.27947815 402.1258197 448.97216125

495.81850281 542.66484436 589.51118591 636.35752747

683.20386902 730.05021057 776.89655212 823.74289368

870.58923523 917.43557678 964.28191833 1011.12825989

1057.97460144 1104.82094299 1151.66728455 1198.5136261

1245.35996765 1292.2063092 1339.05265076 1385.89899231

1432.74533386 1479.59167542 1526.43801697 1573.28435852

1620.13070007 1666.97704163 1713.82338318 1760.66972473]

Lz's attrs: {'min': -2900.541259765625, 'max': 1784.0928955078125}

And displaying the xarray DataArray:

- selection: 1

- Lz: 100

- E: 140

- 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ... 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

array([[[0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0], ..., [0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0]]]) - selection(selection)objectNone

array([None], dtype=object)

- Lz(Lz)float64-2.877e+03 -2.83e+03 ... 1.761e+03

- min :

- -2900.541259765625

- max :

- 1784.0928955078125

array([-2877.118089, -2830.271747, -2783.425406, -2736.579064, -2689.732723, -2642.886381, -2596.04004 , -2549.193698, -2502.347357, -2455.501015, -2408.654673, -2361.808332, -2314.96199 , -2268.115649, -2221.269307, -2174.422966, -2127.576624, -2080.730283, -2033.883941, -1987.037599, -1940.191258, -1893.344916, -1846.498575, -1799.652233, -1752.805892, -1705.95955 , -1659.113209, -1612.266867, -1565.420526, -1518.574184, -1471.727842, -1424.881501, -1378.035159, -1331.188818, -1284.342476, -1237.496135, -1190.649793, -1143.803452, -1096.95711 , -1050.110768, -1003.264427, -956.418085, -909.571744, -862.725402, -815.879061, -769.032719, -722.186378, -675.340036, -628.493694, -581.647353, -534.801011, -487.95467 , -441.108328, -394.261987, -347.415645, -300.569304, -253.722962, -206.87662 , -160.030279, -113.183937, -66.337596, -19.491254, 27.355087, 74.201429, 121.04777 , 167.894112, 214.740453, 261.586795, 308.433137, 355.279478, 402.12582 , 448.972161, 495.818503, 542.664844, 589.511186, 636.357527, 683.203869, 730.050211, 776.896552, 823.742894, 870.589235, 917.435577, 964.281918, 1011.12826 , 1057.974601, 1104.820943, 1151.667285, 1198.513626, 1245.359968, 1292.206309, 1339.052651, 1385.898992, 1432.745334, 1479.591675, 1526.438017, 1573.284359, 1620.1307 , 1666.977042, 1713.823383, 1760.669725]) - E(E)float64-2.414e+05 -2.394e+05 ... 3.495e+04

- min :

- -242407.5

- max :

- 35941.86328125

array([-241413.395131, -239425.185393, -237436.975656, -235448.765918, -233460.55618 , -231472.346443, -229484.136705, -227495.926967, -225507.717229, -223519.507492, -221531.297754, -219543.088016, -217554.878278, -215566.668541, -213578.458803, -211590.249065, -209602.039328, -207613.82959 , -205625.619852, -203637.410114, -201649.200377, -199660.990639, -197672.780901, -195684.571164, -193696.361426, -191708.151688, -189719.94195 , -187731.732213, -185743.522475, -183755.312737, -181767.102999, -179778.893262, -177790.683524, -175802.473786, -173814.264049, -171826.054311, -169837.844573, -167849.634835, -165861.425098, -163873.21536 , -161885.005622, -159896.795884, -157908.586147, -155920.376409, -153932.166671, -151943.956934, -149955.747196, -147967.537458, -145979.32772 , -143991.117983, -142002.908245, -140014.698507, -138026.48877 , -136038.279032, -134050.069294, -132061.859556, -130073.649819, -128085.440081, -126097.230343, -124109.020605, -122120.810868, -120132.60113 , -118144.391392, -116156.181655, -114167.971917, -112179.762179, -110191.552441, -108203.342704, -106215.132966, -104226.923228, -102238.713491, -100250.503753, -98262.294015, -96274.084277, -94285.87454 , -92297.664802, -90309.455064, -88321.245326, -86333.035589, -84344.825851, -82356.616113, -80368.406376, -78380.196638, -76391.9869 , -74403.777162, -72415.567425, -70427.357687, -68439.147949, -66450.938211, -64462.728474, -62474.518736, -60486.308998, -58498.099261, -56509.889523, -54521.679785, -52533.470047, -50545.26031 , -48557.050572, -46568.840834, -44580.631097, -42592.421359, -40604.211621, -38616.001883, -36627.792146, -34639.582408, -32651.37267 , -30663.162932, -28674.953195, -26686.743457, -24698.533719, -22710.323982, -20722.114244, -18733.904506, -16745.694768, -14757.485031, -12769.275293, -10781.065555, -8792.855818, -6804.64608 , -4816.436342, -2828.226604, -840.016867, 1148.192871, 3136.402609, 5124.612347, 7112.822084, 9101.031822, 11089.24156 , 13077.451297, 15065.661035, 17053.870773, 19042.080511, 21030.290248, 23018.499986, 25006.709724, 26994.919461, 28983.129199, 30971.338937, 32959.548675, 34947.758412])

Note that data_array.coords['Lz'].data is the same as Lz_axis.bin_centers and data_array.coords['Lz'].attrs contains the same min/max as the Lz_axis.

Also, we see that displaying the xarray.DataArray object (data_array_view.model.grid) gives us the same output as the data_array_view above. There is a big difference however. If we change a selection:

[6]:

df.select(df.x > 0)

and scroll back we see that the data_array_view widget has updated itself, and now contains two selections! This is a very powerful feature, that allows us to make interactive visualizations.

Interactive plots¶

To make interactive plots we can pass a custom display_function to the data_array_widget. This will override the default notebook behaviour which is a call to display(data_array_widget). In the following example we create a function that displays a matplotlib figure:

[7]:

# NOTE: da is short for 'data array'

def plot2d(da):

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ar = da.data[1] # take the numpy data, and select take the selection

print(f'imshow of a numpy array of shape: {ar.shape}')

plt.imshow(np.log1p(ar.T), origin='lower')

df.widget.data_array(axes=[Lz_axis, E_axis], display_function=plot2d, selection=[None, True])

In the above figure, we choose index 1 along the selection axis, which referes to the 'default' selection. Choosing an index of 0 would correspond to the None selection, and all the data would be displayed. If we now change the selection, the figure will update itself:

[8]:

df.select(df.id < 10)

As xarray’s DataArray is fully self describing, we can improve the plot by using the dimension names for labeling, and setting the extent of the figure’s axes.

Note that we don’t need any information from the Axis objects created above, and in fact, we should not use them, since they may not be in sync with the xarray DataArray object. Later on, we will create a widget that will edit the Axis’ expression.

Our improved visualization with proper axes and labeling:

[9]:

def plot2d_with_labels(da):

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

grid = da.data # take the numpy data

dim_x = da.dims[0]

dim_y = da.dims[1]

plt.title(f'{dim_y} vs {dim_x} - shape: {grid.shape}')

extent = [

da.coords[dim_x].attrs['min'], da.coords[dim_x].attrs['max'],

da.coords[dim_y].attrs['min'], da.coords[dim_y].attrs['max']

]

plt.imshow(np.log1p(grid.T), origin='lower', extent=extent, aspect='auto')

plt.xlabel(da.dims[0])

plt.ylabel(da.dims[1])

da_plot_view_nicer = df.widget.data_array(axes=[Lz_axis, E_axis], display_function=plot2d_with_labels)

da_plot_view_nicer

We can also create more sophisticated plots, for example one where we show all of the selections. Note that we can pre-emptively expect a selection and define it later:

[10]:

def plot2d_with_selections(da):

grid = da.data

# Create 1 row and #selections of columns of matplotlib axes

fig, axgrid = plt.subplots(1, grid.shape[0], sharey=True, squeeze=False)

for selection_index, ax in enumerate(axgrid[0]):

ax.imshow(np.log1p(grid[selection_index].T), origin='lower')

df.widget.data_array(axes=[Lz_axis, E_axis], display_function=plot2d_with_selections,

selection=[None, 'default', 'rest'])

Modifying a selection will update the figure.

[11]:

df.select(df.id < 10) # select 10 objects

df.select(df.id >= 10, name='rest') # and the rest

Another advantage of using xarray is its excellent plotting capabilities. It handles a lot of the boring stuff like axis labeling, and also provides a nice interface for slicing the data even more.

Let us introduce another axis, FeH (fun fact: FeH is a property of stars that tells us how much iron relative to hydrogen is contained in them, an idicator of their origin):

[12]:

FeH_axis = vjm.Axis(df=df, expression='FeH', min=-3, max=1, shape=5)

da_view = df.widget.data_array(axes=[E_axis, Lz_axis, FeH_axis], selection=[None, 'default'])

da_view

We can see that we now have a 4 dimensional grid, which we would like to visualize.

And xarray’s plot make our life much easier:

[13]:

def plot_with_xarray(da):

da_log = np.log1p(da) # Note that an xarray DataArray is like a numpy array

da_log.plot(x='Lz', y='E', col='FeH', row='selection', cmap='viridis')

plot_view = df.widget.data_array([E_axis, Lz_axis, FeH_axis], display_function=plot_with_xarray,

selection=[None, 'default', 'rest'])

plot_view

We only have to tell xarray which axis it should map to which ‘aesthetic’, speaking in Grammar of Graphics terms.

Selection widgets¶

Although we can change the selection in the notebook (e.g. df.select(df.id > 20)), if we create a dashboard (using Voila) we cannot execute arbitrary code. Vaex-jupyter also comes with many widgets, and one of them is a selection_expression widget:

[14]:

selection_widget = df.widget.selection_expression()

selection_widget

The counter_selection creates a widget which keeps track of the number of rows in a selection. In this case we ask it to be ‘lazy’, which means that it will not cause extra passes over the data, but will ride along if some user action triggers a calculation.

[15]:

await vaex.jupyter.gather()

w = df.widget.counter_selection('default', lazy=True)

w

Axis control widgets¶

Let us create new axis objects using the same expressions as before, but give them more general names (x_axis and y_axis), because we want to change the expressions interactively.

[16]:

x_axis = vjm.Axis(df=df, expression=df.Lz)

y_axis = vjm.Axis(df=df, expression=df.E)

da_xy_view = df.widget.data_array(axes=[x_axis, y_axis], display_function=plot2d_with_labels, shape=180)

da_xy_view

Again, we can change the expressions of the axes programmatically:

[17]:

# wait for the previous plot to finish

await vaex.jupyter.gather()

# Change both the x and y axis

x_axis.expression = np.log(df.x**2)

y_axis.expression = df.y

# Note that both assignment will create 1 computation in the background (minimal amount of passes over the data)

await vaex.jupyter.gather()

# vaex computed the new min/max, and the xarray DataArray

# x_axis.min, x_axis.max, da_xy_view.model.grid

But, if we want to create a dashboard with Voila, we need to have a widget that controls them:

[18]:

x_widget = df.widget.expression(x_axis.expression, label='X axis')

x_widget

This widget will allow us to edit an expression, which will be validated by Vaex. How do we ‘link’ the value of the widget to the axis expression? Because both the Axis as well as the x_widget are HasTrait objects, we can link their traits together:

[19]:

from ipywidgets import link

link((x_widget, 'value'), (x_axis, 'expression'))

[19]:

<traitlets.traitlets.link at 0x122bed450>

Since this operation is so common, we can also directly pass the Axis object, and Vaex will set up the linking for us:

[20]:

y_widget = df.widget.expression(y_axis, label='X axis')

# vaex now does this for us, much shorter

# link((y_widget, 'value'), (y_axis, 'expression'))

y_widget

[21]:

await vaex.jupyter.gather() # lets wait again till all calculations are finished

A nice container¶

If you are familiar with the ipyvuetify components, you can combine them to create very pretty widgets. Vaex-jupyter comes with a nice container:

[22]:

from vaex.jupyter.widgets import ContainerCard

ContainerCard(title='My plot',

subtitle="using vaex-jupyter",

main=da_xy_view,

controls=[x_widget, y_widget], show_controls=True)

We can directly assign a Vaex expression to the x_axis.expression, or to x_widget.value since they are linked.

[23]:

y_axis.expression = df.vx

Interactive plots¶

So far we have been using interactive widgets to control the axes in the view. The figure itself however was not interactive, and we could not have panned or zoomed for example.

Vaex has a few builtin visualizations, most notably a heatmap and histogram using bqplot:

[24]:

df = vaex.example() # we create the dataframe again, to leave all the plots above 'alone'

heatmap_xy = df.widget.heatmap(df.x, df.y, selection=[None, True])

heatmap_xy

Note that we passed expressions, and not axis objects. Vaex recognizes this and will create the axis objects for you. You can access them from the model:

[25]:

heatmap_xy.model.x

[25]:

Axis(bin_centers=[-77.7255446 -76.91058156 -76.09561852 -75.28065547 -74.46569243

-73.65072939 -72.83576635 -72.0208033 -71.20584026 -70.39087722

-69.57591417 -68.76095113 -67.94598809 -67.13102505 -66.316062

-65.50109896 -64.68613592 -63.87117288 -63.05620983 -62.24124679

-61.42628375 -60.6113207 -59.79635766 -58.98139462 -58.16643158

-57.35146853 -56.53650549 -55.72154245 -54.90657941 -54.09161636

-53.27665332 -52.46169028 -51.64672723 -50.83176419 -50.01680115

-49.20183811 -48.38687506 -47.57191202 -46.75694898 -45.94198593

-45.12702289 -44.31205985 -43.49709681 -42.68213376 -41.86717072

-41.05220768 -40.23724464 -39.42228159 -38.60731855 -37.79235551

-36.97739246 -36.16242942 -35.34746638 -34.53250334 -33.71754029

-32.90257725 -32.08761421 -31.27265117 -30.45768812 -29.64272508

-28.82776204 -28.01279899 -27.19783595 -26.38287291 -25.56790987

-24.75294682 -23.93798378 -23.12302074 -22.3080577 -21.49309465

-20.67813161 -19.86316857 -19.04820552 -18.23324248 -17.41827944

-16.6033164 -15.78835335 -14.97339031 -14.15842727 -13.34346423

-12.52850118 -11.71353814 -10.8985751 -10.08361205 -9.26864901

-8.45368597 -7.63872293 -6.82375988 -6.00879684 -5.1938338

-4.37887076 -3.56390771 -2.74894467 -1.93398163 -1.11901858

-0.30405554 0.5109075 1.32587054 2.14083359 2.95579663

3.77075967 4.58572271 5.40068576 6.2156488 7.03061184

7.84557489 8.66053793 9.47550097 10.29046401 11.10542706

11.9203901 12.73535314 13.55031618 14.36527923 15.18024227

15.99520531 16.81016836 17.6251314 18.44009444 19.25505748

20.07002053 20.88498357 21.69994661 22.51490965 23.3298727

24.14483574 24.95979878 25.77476183 26.58972487 27.40468791

28.21965095 29.034614 29.84957704 30.66454008 31.47950312

32.29446617 33.10942921 33.92439225 34.7393553 35.55431834

36.36928138 37.18424442 37.99920747 38.81417051 39.62913355

40.4440966 41.25905964 42.07402268 42.88898572 43.70394877

44.51891181 45.33387485 46.14883789 46.96380094 47.77876398

48.59372702 49.40869007 50.22365311 51.03861615 51.85357919

52.66854224 53.48350528 54.29846832 55.11343136 55.92839441

56.74335745 57.55832049 58.37328354 59.18824658 60.00320962

60.81817266 61.63313571 62.44809875 63.26306179 64.07802483

64.89298788 65.70795092 66.52291396 67.33787701 68.15284005

68.96780309 69.78276613 70.59772918 71.41269222 72.22765526

73.0426183 73.85758135 74.67254439 75.48750743 76.30247048

77.11743352 77.93239656 78.7473596 79.56232265 80.37728569

81.19224873 82.00721177 82.82217482 83.63713786 84.4521009

85.26706395 86.08202699 86.89699003 87.71195307 88.52691612

89.34187916 90.1568422 90.97180524 91.78676829 92.60173133

93.41669437 94.23165742 95.04662046 95.8615835 96.67654654

97.49150959 98.30647263 99.12143567 99.93639871 100.75136176

101.5663248 102.38128784 103.19625089 104.01121393 104.82617697

105.64114001 106.45610306 107.2710661 108.08602914 108.90099218

109.71595523 110.53091827 111.34588131 112.16084436 112.9758074

113.79077044 114.60573348 115.42069653 116.23565957 117.05062261

117.86558565 118.6805487 119.49551174 120.31047478 121.12543783

121.94040087 122.75536391 123.57032695 124.38529 125.20025304

126.01521608 126.83017913 127.64514217 128.46010521 129.27506825

130.0900313 ], exception=None, expression=x, max=130.4975128173828, min=-78.13302612304688, shape=None, shape_default=256, slice=None, status=Status.READY)

The heatmap itself is again a widget. Thus we can combine it with other widgets to create a more sophisticated interface.

[26]:

x_widget = df.widget.expression(heatmap_xy.model.x, label='X axis')

y_widget = df.widget.expression(heatmap_xy.model.y, label='X axis')

ContainerCard(title='My plot',

subtitle="using vaex-jupyter and bqplot",

main=heatmap_xy,

controls=[x_widget, y_widget, selection_widget],

show_controls=True,

card_props={'style': 'min-width: 800px;'})

By switching the tool in the toolbar (click pan_tool, or changing it programmmatically in the next cell), we can zoom in. The plot’s axis bounds are directly synched to the axis object (the x_min is linked to the x_axis min, etc). Thus a zoom action causes the axis objects to be changed, which will trigger a recomputation.

[27]:

heatmap_xy.tool = 'pan-zoom' # we can also do this programmatically.

Since we can access the Axis objects, we can also programmatically change the heatmap. Note that both the expression widget, the plot axis label and the heatmap it self is updated. Everything is linked together!

[28]:

heatmap_xy.model.x.expression = np.log10(df.x**2)

await vaex.jupyter.gather() # and we wait before we continue

Another visualization based on bqplot is the interactive histogram. In the example below, we show all the data, but the selection interaction will affect/set the ‘default’ selection.

[29]:

histogram_Lz = df.widget.histogram(df.Lz, selection_interact='default')

histogram_Lz.tool = 'select-x'

histogram_Lz

[30]:

# You can graphically select a particular region, in this case we do it programmatically

# for reproducability of this notebook

histogram_Lz.plot.figure.interaction.selected = [1200, 1300]

This shows an interesting structure in the heatmap above

Creating your own visualizations¶

The primary goal of Vaex-Jupyter is to provide users with a framework to create dashboard and new visualizations. Over time more visualizations will go into the vaex-jupyter package, but giving you the option to create new ones is more important. To help you create new visualization, we have examples on how to create your own:

If you want to create your own visualization on this framework, check out these examples:

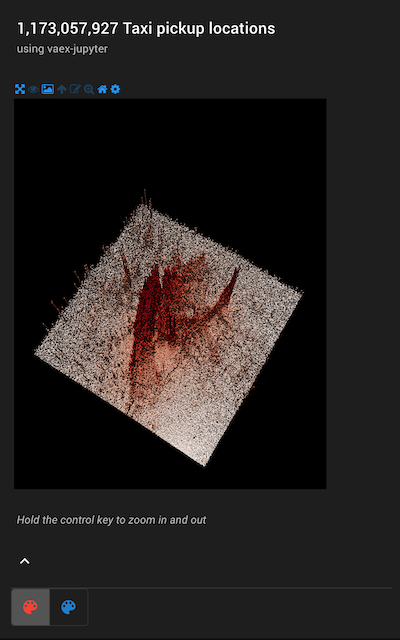

ipyvolume example¶

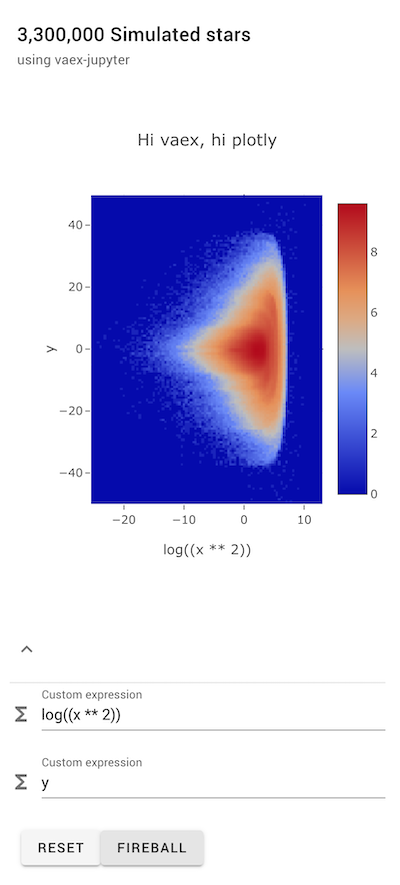

plotly example¶

The examples can also be found at the Examples page.